Rockhopper Penguins (Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome) are the smallest of the crested penguins with a circumpolar distribution. They are also one of the most common penguin species in the Falklands. The penguins which weigh between 2 and 2.7 kg get their name because they move around by hopping keeping both feet together. Despite, what may seem as hindrance, they are exceptionally agile on land; I was constantly amazed by their ability to tackle the most challenging terrain as they ledge-hopped on precipitous cliff faces!

Rockhopper Penguins (Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome) are the smallest of the crested penguins with a circumpolar distribution. They are also one of the most common penguin species in the Falklands. The penguins which weigh between 2 and 2.7 kg get their name because they move around by hopping keeping both feet together. Despite, what may seem as hindrance, they are exceptionally agile on land; I was constantly amazed by their ability to tackle the most challenging terrain as they ledge-hopped on precipitous cliff faces!

If you inspect the cliffs closely you can see the narrow cuts and crevices created by the sharp toe claws on the penguin s feet. The carved sandstone provided evidence to the millions of penguins that have moved across the rock over thousands of years.

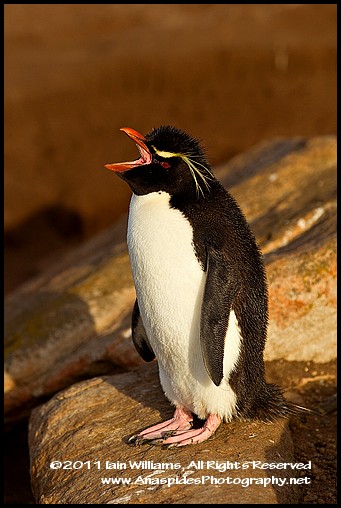

LEFT: After an arduous cllimb of 50 meters, a rockhopper penguin bellows its success in the late afternoon light.

Every evening the rockhoppers porpoise towards the steep sea cliffs riding the large South Atlantic swells. More than once the penguins, who gather into a raft for safety just out from the breakers, are pulverised onto the sharp rocks. I watched a small group land successfully onto a flat rock and begin to hop to safety only to be swept away again by another large wave. If this is not enough, predators cruise the coast near the breeding colonies seeking an easy kill. Southern elephant seals, leapoard seals and killer whales regularly lie in ambush waiting for the penguins to begin their waterborne assault.

Rockhoppers live in large colonies often mixed with albatross or imperial shags. They are noisy and quarrelsome little creatures but their comical antics and inquisitive personalities make them very endearing and they soon become the favourite penguin for many visitors.

Currently they listed as vulnerable by several conservation agencies with an overall decline in most populations. The speculated reason for this decline is the rise in sea surface temperature (due to global warming) which has affected the prey stocks of rockhopper penguins.

Breeding

Breeding

Rockhopper penguins are very synchronised in their breeding cycle both within a colony and across years. Males return to the island in mid-October and females a few days later. Nests are re-established (with most returning to the same nest sites and mates) and two eggs laid, with the smaller first egg never producing a chick to fledging.

LEFT: The afternoon rush hour as food-ladden rockhopper penguins make their way to the colony to rejoin their mate and offspring

Females take the first incubation shift while males, who have not eaten for some 4 weeks, go to sea to forage. On the males return, the females depart for a foraging trip and return as the chicks hatch. Females provide all food for the chick when it is young and when absent from the nest (food foraging) the male will undertake guard duty. But once chicks enter a creche, both parents forage.

Chicks fledge at the end of February. At this time adults go to sea to fatten for the moult, which they undertake in early March. After finishing the moult they depart the breeding areas in late April.

Diet and Feeding

Diet and Feeding

Rockhopper penguins eat predominantly euphausiids, myctophid fish and squid which they hunt for in the Polar Frontal, Zone.

LEFT: Rockhopper penguins on the move. It's amazing the speed they can travel at by hopping.

In my next Falklands post, we will discuss the largest seabird that breeds on the Falklands the Black-browed Albatross.